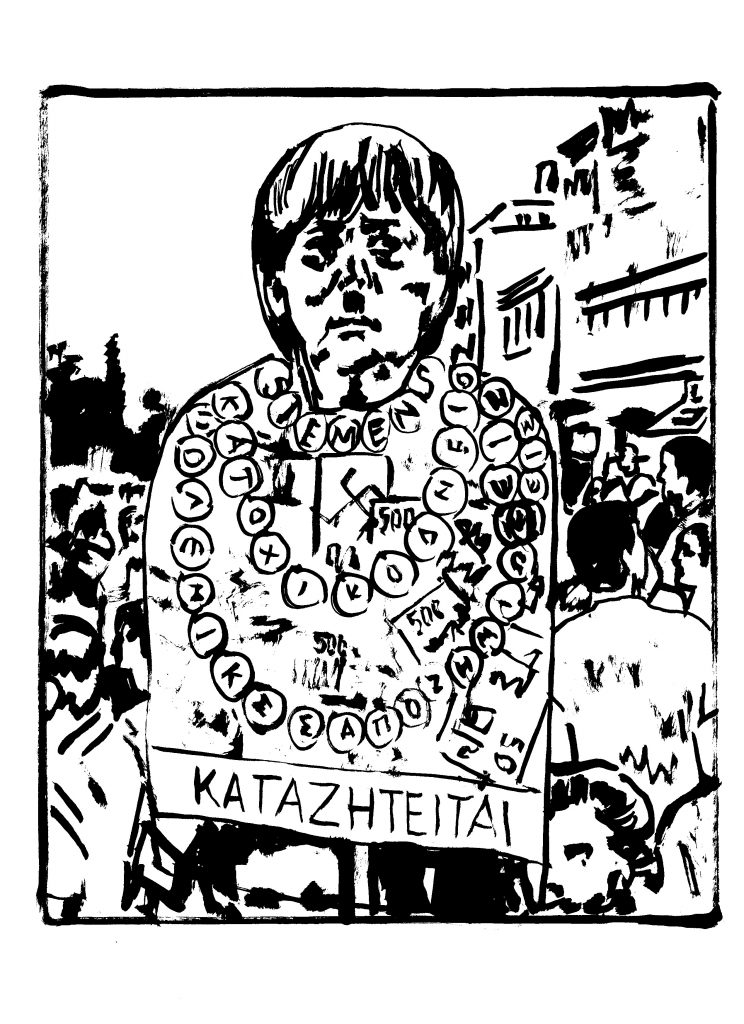

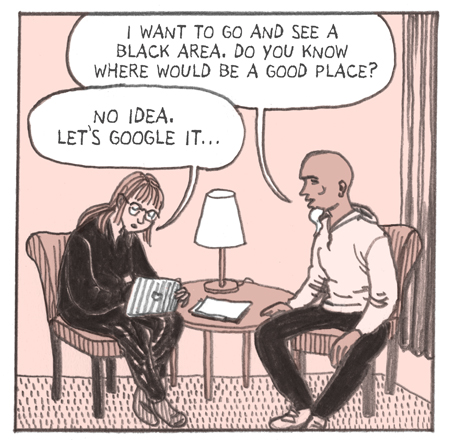

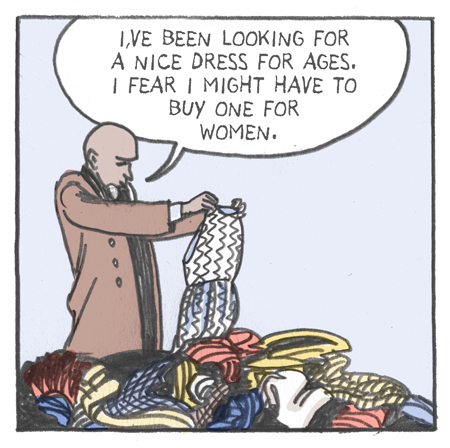

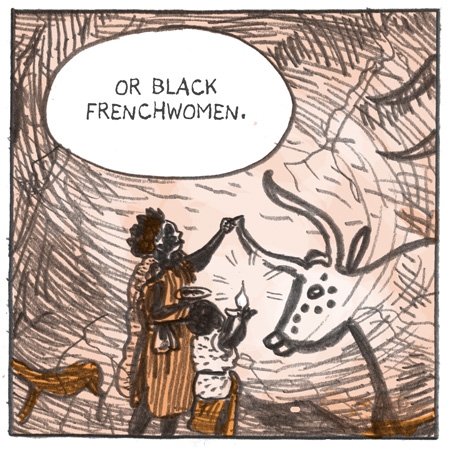

We go into an evangelical church. The architecture is neither Romanesque or Gothic; it’s probably an old cinema or theatre. In France, churches like these make do with more sober venues or are situated way out on the urban peripheries. An enthusiastic young woman greets us warmly. A shadow passes across her face when Ulli tells her she only knows one word of Nigerian: Oibo, which means white. It’s not necessarily a friendly word. We hear hymns being sung and would like to attend the service, but we’re wasting our time: that service isn’t for us. There’s another one we’re most welcome to attend, if we’d like. Probably because we’re oibos. Me, too, I’m an oibo. When I lived in Benin between the ages of six and nine I was yovo, white. White in Africa, black in France. Sometimes the French use the English word black; it sounds cooler. Black and French. White and Beninese. Cool.

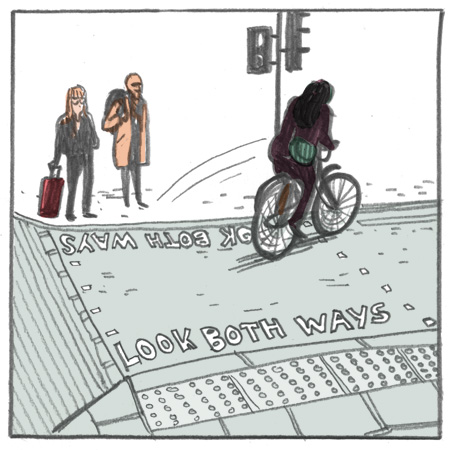

Being born on a boundary is to be keenly aware that it doesn’t exist, while at the same time experiencing its existence in the social world. Once, my mum cried in my arms when I told her that the things she said about Africans were racist. She cried at the memory of all she’d had to put up with, particularly from her dad, for having married an African, a black, a Negro, a darkie—or whatever you want to say.

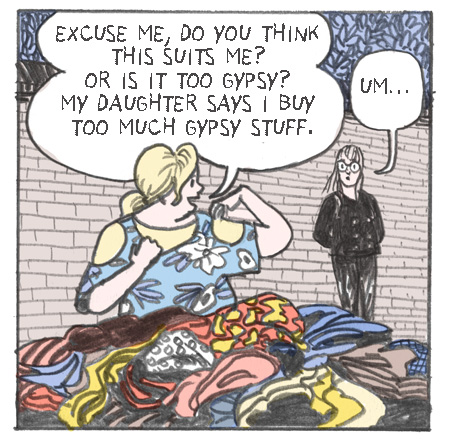

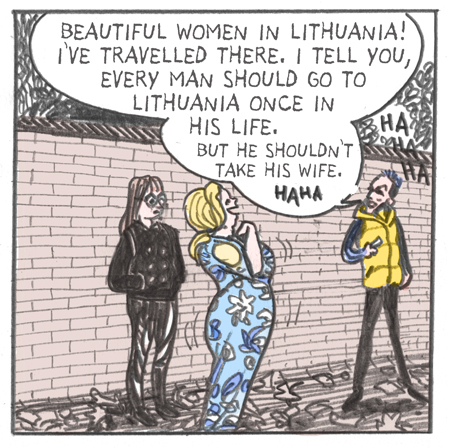

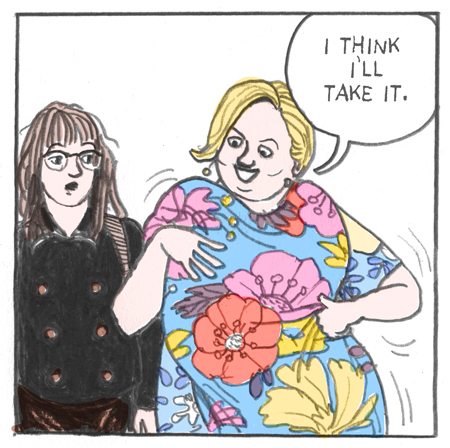

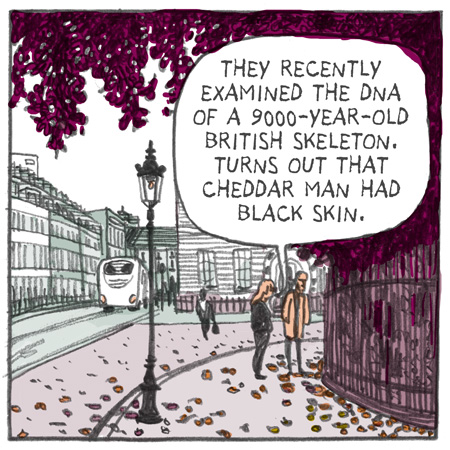

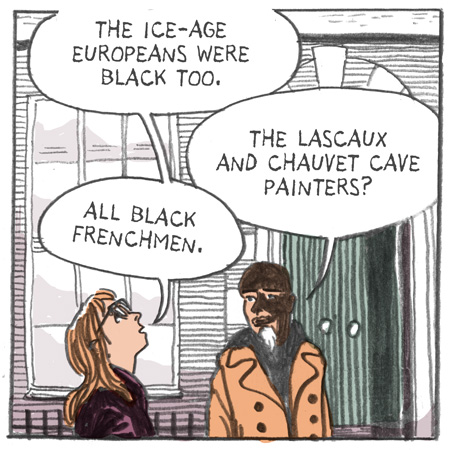

The black Frenchman is talking to the Austrian woman. The wogs are talking to the wogs. The wogs talk to everyone, because everyone’s a wog. We’re currently working on Europe. My tailor has a mule. Flora has a red neck. I like foie gras.

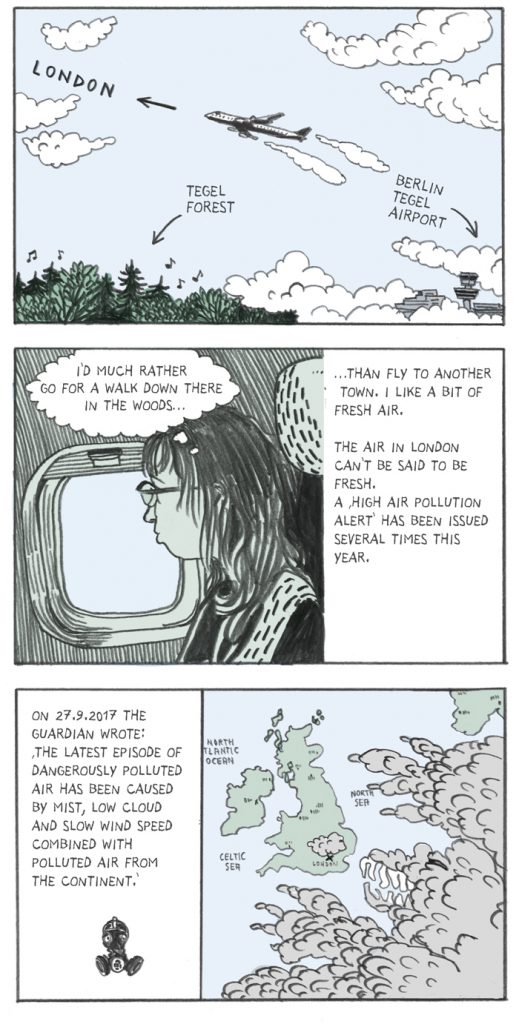

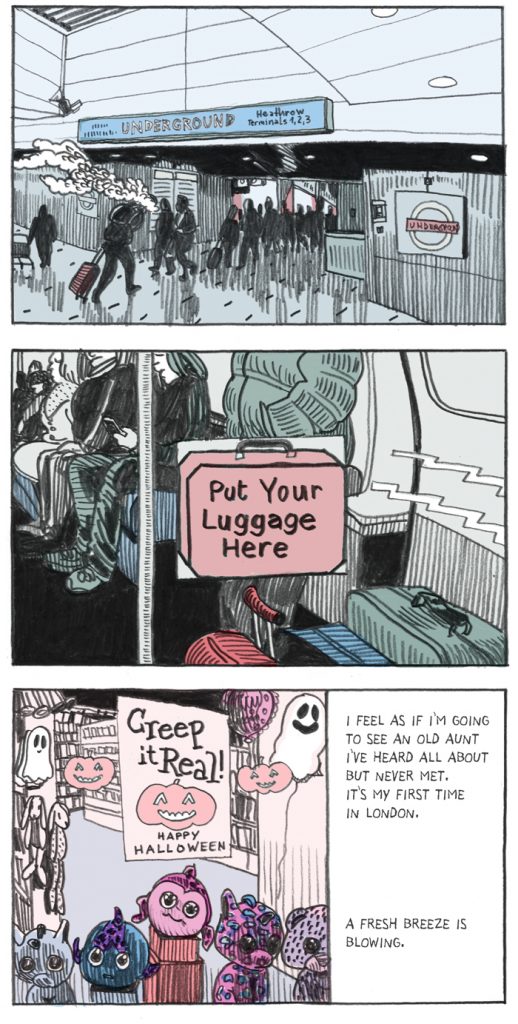

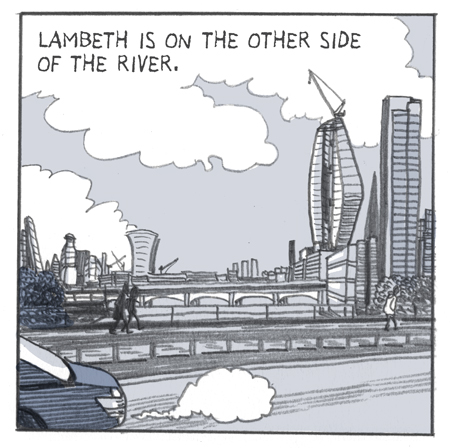

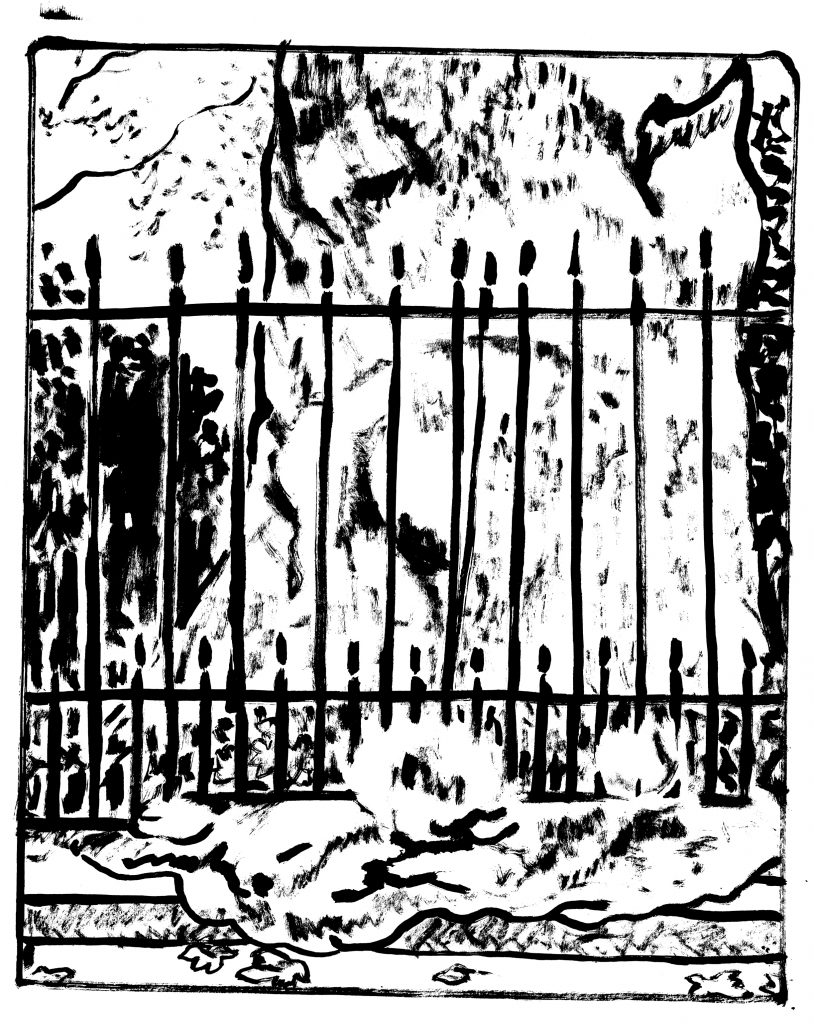

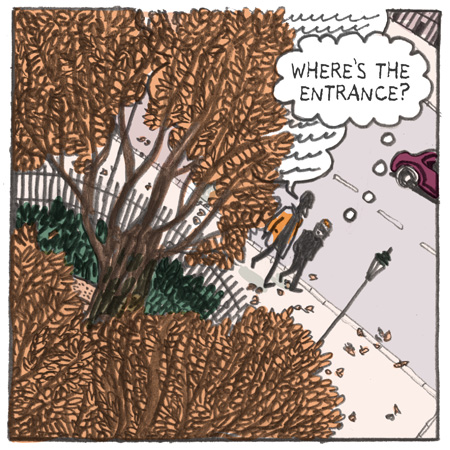

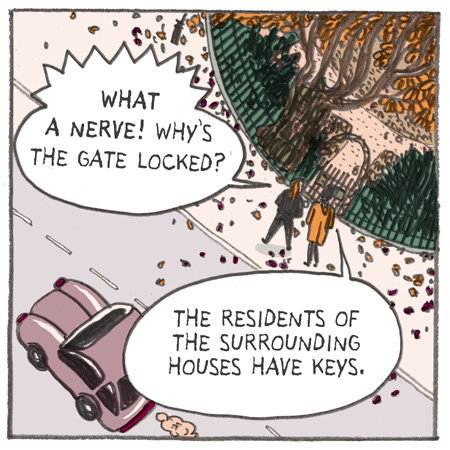

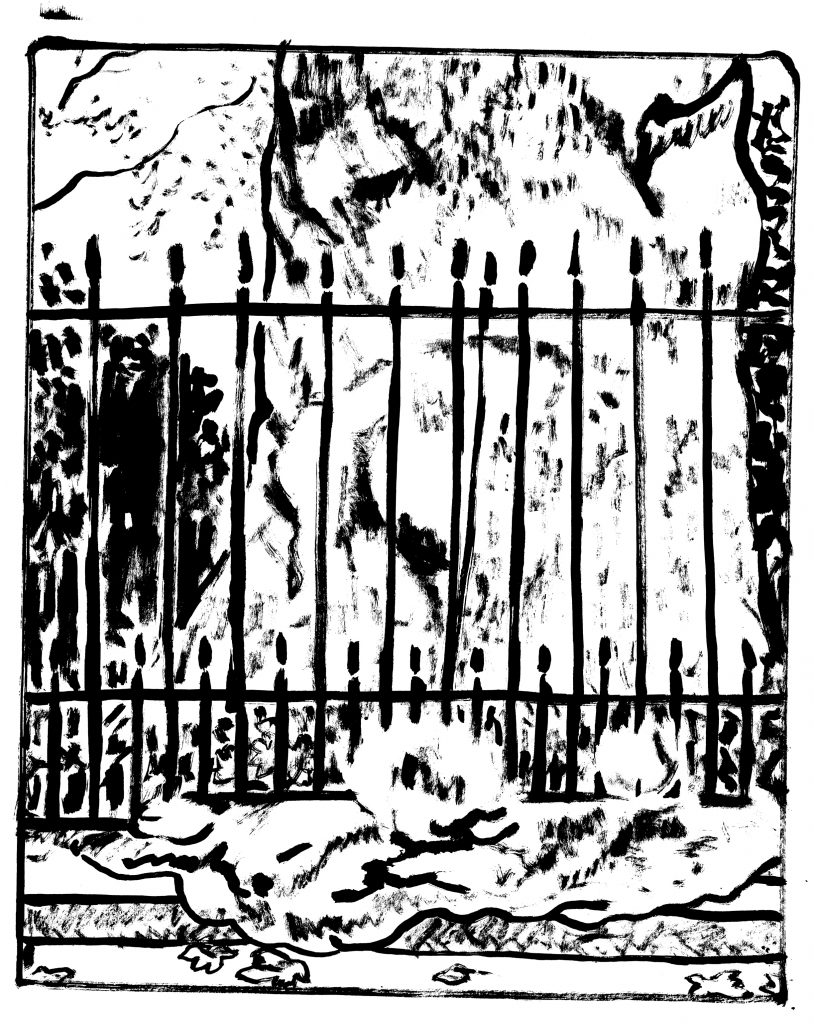

This is London. Just down the road from the hotel is a square of immaculate Georgian buildings with a circular garden in the centre. One morning, I walk round this garden, looking for the entrance. I am staggered to discover that what I had assumed was a public square is, in fact, private. Only the residents of the square have keys. I’ve never seen anything like it in Paris or anywhere else, where secret gardens like this are hidden from view. Inquiries reveal that it’s not the only one of its kind in London, although they are rare, the legacy of a bygone age. It glows with serene sovereignty, like privilege made visible, an ode to private property. I have a strong feeling that this ‘caging’ of Nature is Man’s way of expressing its essence, its appeal, but also its limits.

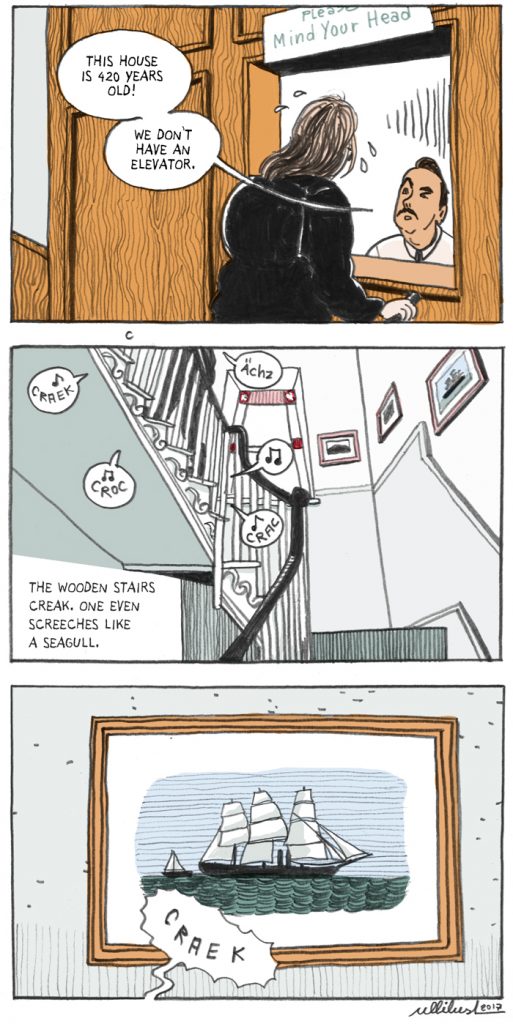

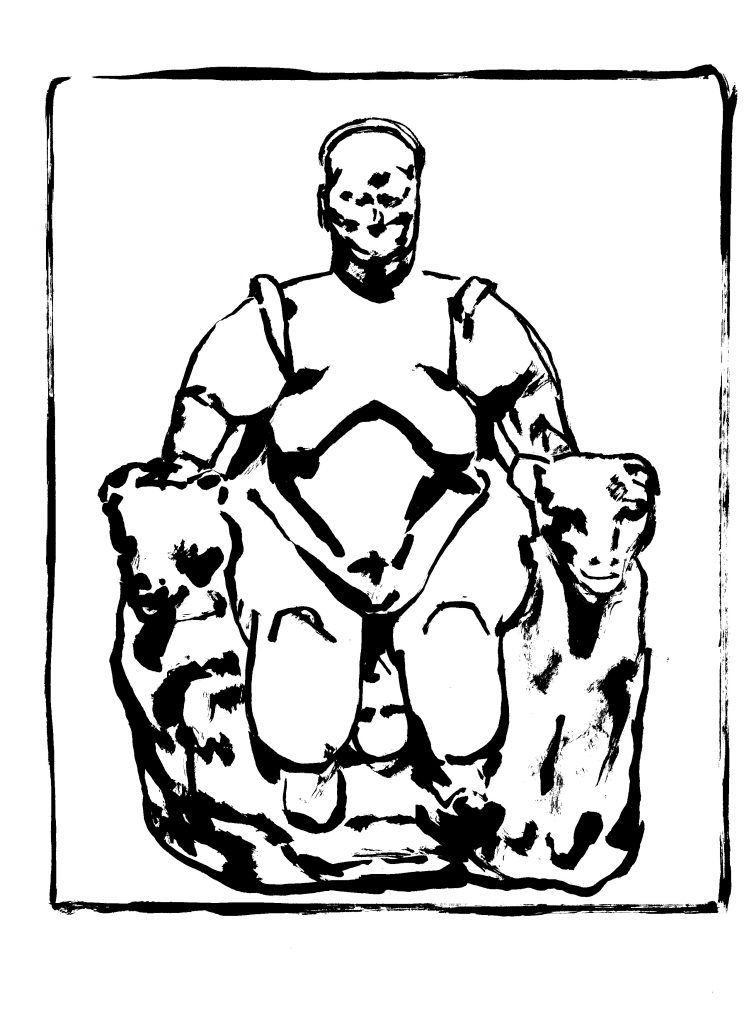

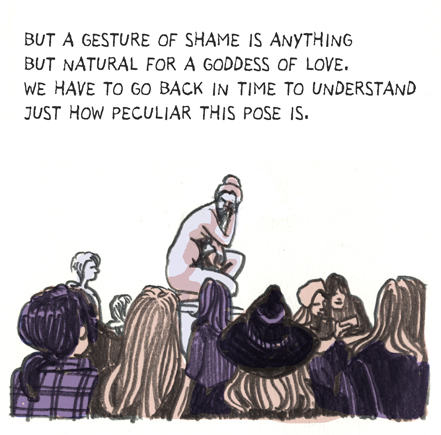

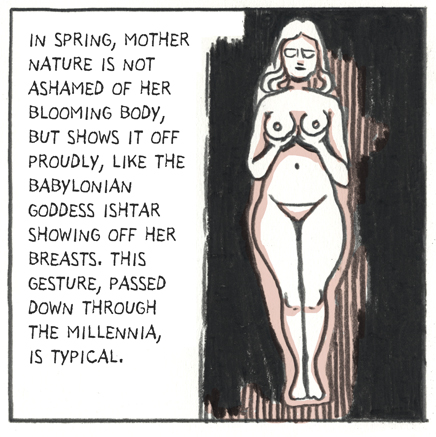

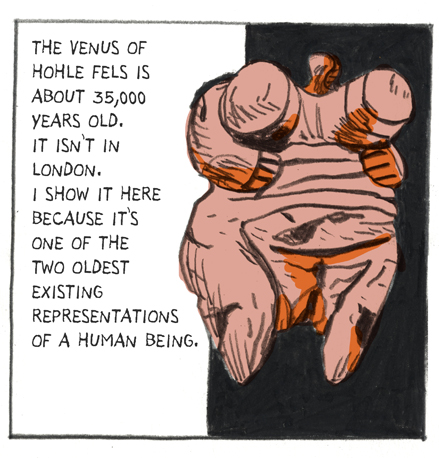

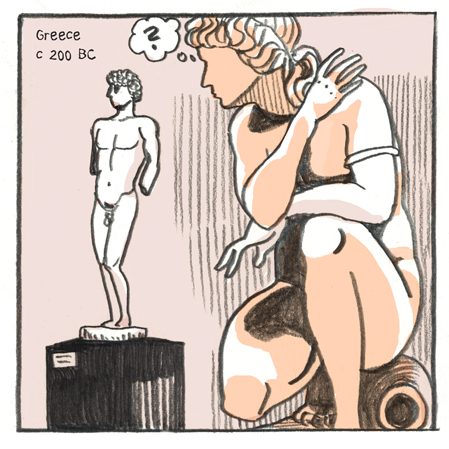

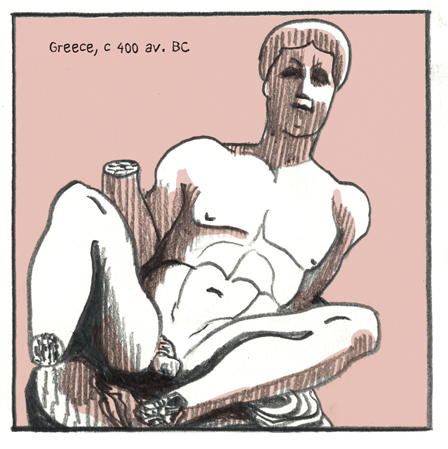

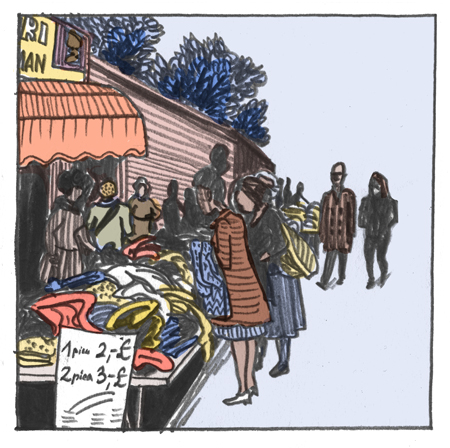

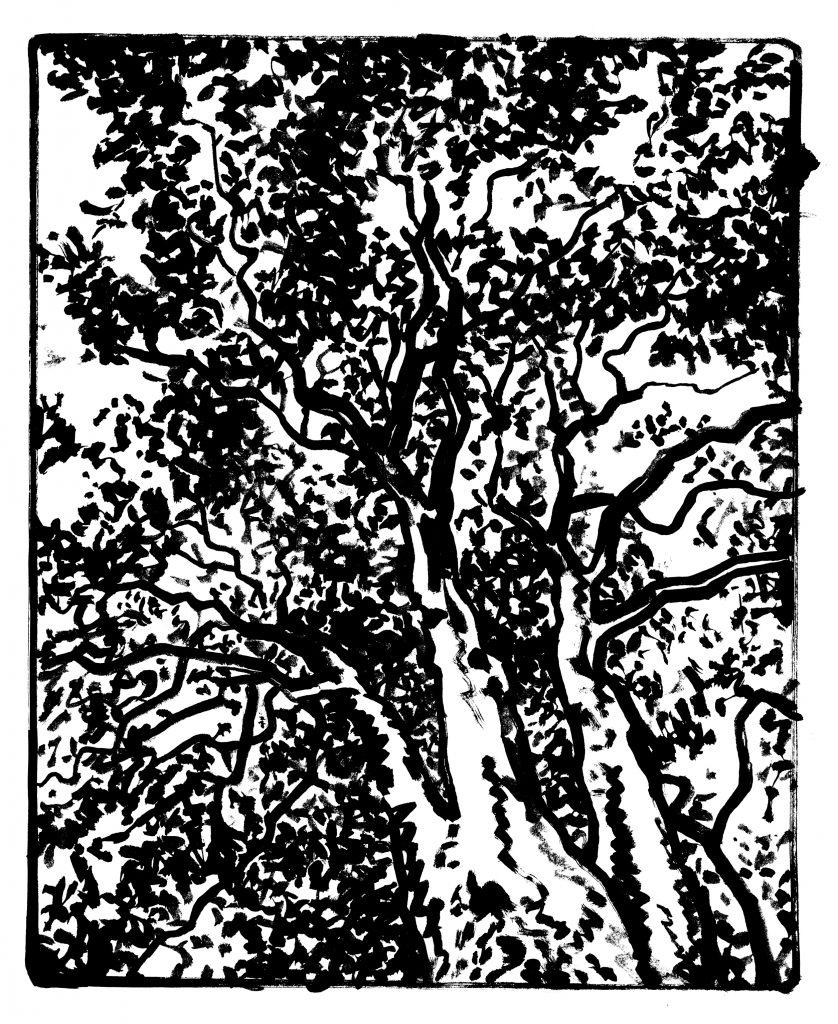

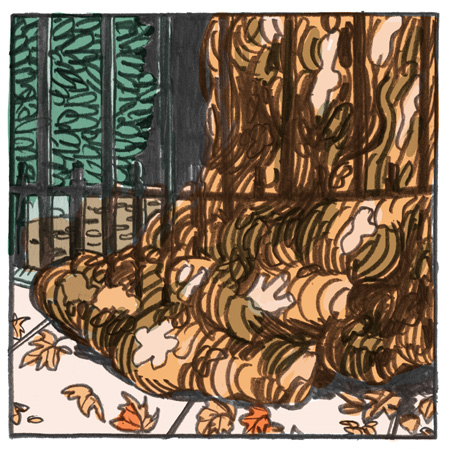

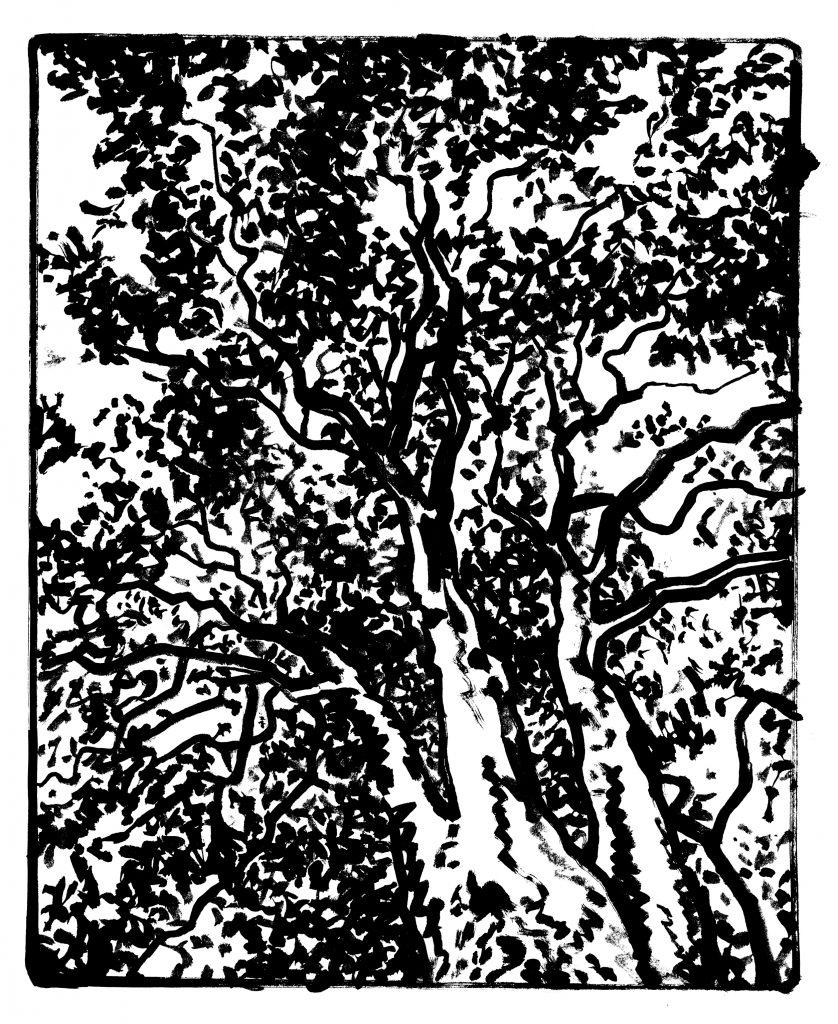

In the evening, after an abortive pilgrimage towards Brixton—I show Ulli this square. We walk round it in the light of the lampposts, smoking. We look at the century-old trees growing by the fence, bulging out of it, brimming over it, swallowing it up, their breasts, bellies and muscles swollen. The force at work here has no limits. If we can’t see it, that’s because it’s slow. Because we’re walking too fast. Because our lives are too short. And so we talk about religion; I may have taken the crazy gamble of writing a History of Love, but at least I learnt this from it: when the pagan religions died out, the goddesses died out with them—especially the Great Goddess. Black and beautiful as the night.

Ulli tells me about the trees’ spirit, floating a few metres above their branches. When I get back to my room, I finally make a start on the William Blake poems. And I come across a sentence that brings me back, in a way, to the task we’ve been assigned: ‘The Religions of all Nations are derived from each Nation’s different reception of the Poetic Genius, which is everywhere call’d the Spirit of Prophecy.’ All Religions are One, the title of the pamphlet proclaims.

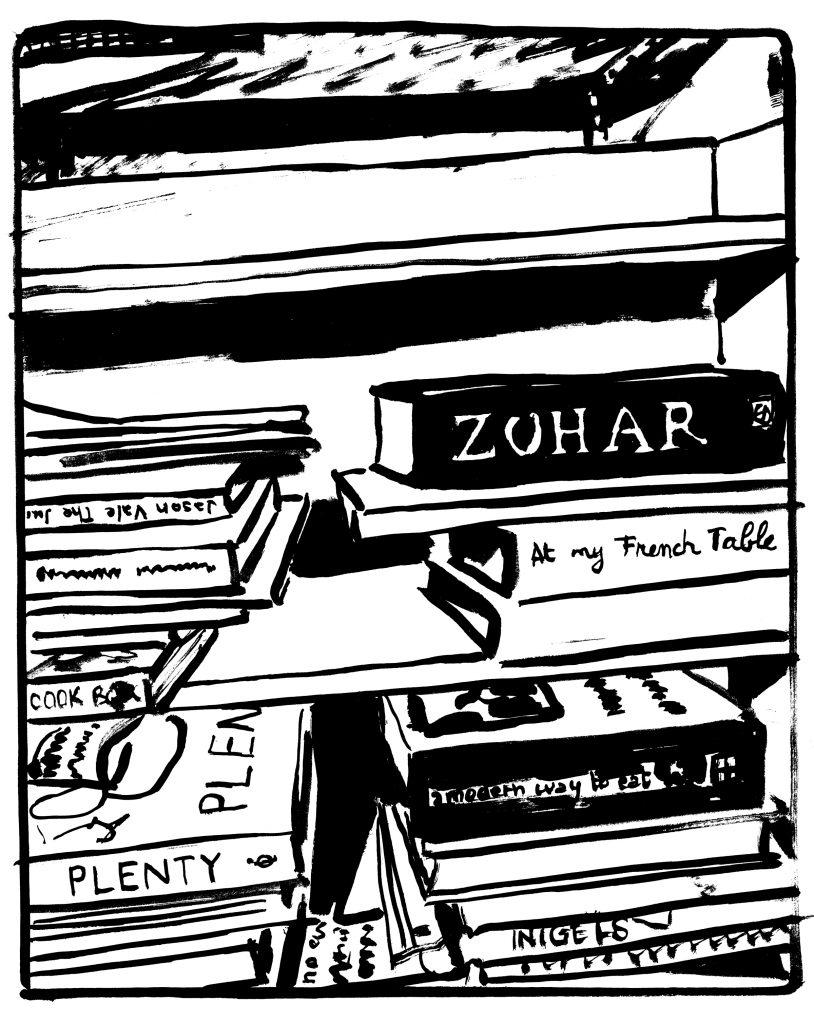

I don’t know what William Blake means by ‘Spirit of Prophecy’ but I do, I’m afraid, sometimes have the feeling I’m turning into a prophet. A rather helpless and pathetic prophet, but still. It all began when I started reading Karl Polyani. I’ve seen no trace of Karl Polyani in London, even though he once lived here. He was born in Vienna, like Mozart and Ulli, only in 1866, and ended up on the Hungarian side of the Austro-Hungarian empire. In 1933 he left Vienna for London, fleeing the rise to power of you-know-who. In England, he taught economic history and collected memories of the origins of the English working class. It was to this period that he owed his major work, The Great Transformation, where he traces the origins of the utopia of a free market. If you ponder the upheavals in today’s Europe, the return of certain ghosts from the past and the neoliberal dictatorship, you might be forgiven for predicting the fall of the golden calf. Like its earlier counterparts, our sad empire is hurtling faster and faster towards its end. Which will be when? I have no idea, of course. A prophet of doom, but not a seer. Not an apostle of heaven or hell either.

The wild boars are on the loose. I repeat, the wild boars are on the loose. Don’t get hypnotised or trapped by the spectacle of disaster. Remain present, give yourself to Joy. Only one ‘bloody standard’. Love. The acacias are Marie’s roses. Fernande is in love.

© Yvan Alagbé